The Tale of Genji: The World’s First Novel and the Woman Who Wrote It

When people talk about the great literary works of the world, names like Shakespeare, Homer, and Dante are often at the top of the list. But long before many of those names made their mark, a Japanese noblewoman was quietly writing what is now considered by many scholars to be the world’s first novel: The Tale of Genji. Not only is it an extraordinary feat of storytelling, but it also stands as a powerful reminder of the creative brilliance of women, especially in times when their voices were not always welcome.

Lately, I’ve been reflecting on my own Japanese heritage, and in doing so, I found myself returning to Genji Monogatari, or The Tale of Genji. This thousand-year-old masterpiece is more than just a novel. It’s a window into the aristocratic court life of the Heian period (794 to 1185), a poetic meditation on love and loss, and a striking act of authorship during a time when women were rarely seen as writers of record.

Not many people know this about me, but I actually spent my high school years growing up in Tokyo. And strangely enough, the class I enjoyed most was called “Koten,” a study of classical Japanese literature. (Ironically, I could barely pass my regular Japanese classes.) I think I’ve always been drawn to stories that leave breadcrumbs—fragments of the author’s intentions or inner world scattered between the lines. I like a good puzzle, and trying to figure out what an author meant was always a sort of hobby of mine.

As I reflect on The Tale of Genji this May during Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, I’m reminded that honoring heritage isn’t just about looking back—it’s also about listening to the voices that came before us and letting them shape the way we create today.

Let’s explore why The Tale of Genji remains so important and how its author broke the mold in more ways than one.

What Is The Tale of Genji About?

Written in the early 11th century, The Tale of Genji follows the life and romantic exploits of Hikaru Genji, the “Shining Prince.” The story begins with Genji’s birth. He is the son of an emperor and a low-ranking concubine, and the novel follows him through a life of courtly love, ambition, heartbreak, and personal reflection. Genji is intelligent, refined, and devastatingly charming, and much of the novel is devoted to his complex relationships with women, many of whom love him deeply, but not always happily.

The plot stretches across 54 chapters and spans several generations, evolving from Genji’s personal story into that of his descendants. While the narrative focuses heavily on romantic relationships, it also paints a detailed portrait of Heian aristocratic culture: the music, poetry, clothing, seasonal rituals, and political tensions of the time. It’s not just a love story. It’s a rich tapestry of Japanese court life, full of subtle emotion and human complexity.

Who Wrote It and Why That Matters

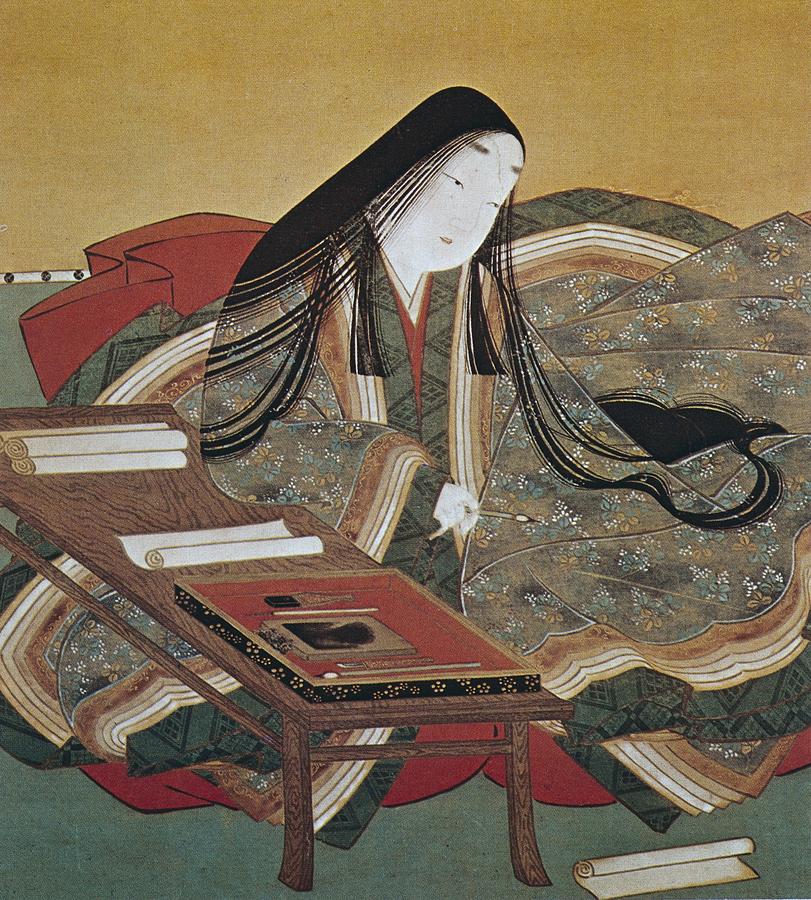

The author of The Tale of Genji is Murasaki Shikibu, a noblewoman and lady-in-waiting at the Heian court. Her real name is unknown. “Murasaki” is a reference to one of the female characters in the story, and “Shikibu” refers to her father’s position in the government. Like many women of her time, she was not permitted to publish under her own name, and yet, her work has outlived centuries.

What makes Murasaki Shikibu’s achievement even more impressive is the context in which she was writing. During the Heian period, elite women were educated, but their learning was often limited to poetry, etiquette, and the Japanese kana scripts, namely hiragana, a phonetic writing system that had only recently developed at the time. Men, on the other hand, studied kanji, the Chinese characters considered the language of official discourse, scholarly writing, and serious literature.

Writing in hiragana was seen as more informal and distinctly feminine, an association that was often viewed as inferior at the time. But it was exactly this script that allowed women like Murasaki to carve out a literary space of their own. In this “women’s script,” she penned an emotionally nuanced and structurally sophisticated story that has endured for over a millennium.

The fact that The Tale of Genji was written in kana, and not kanji, is not just a technical note. It’s a reflection of gendered expression. While men were writing Chinese poetry and political treatises, women were quietly building an entirely new literary tradition in their own language. Murasaki Shikibu turned what was viewed as a limitation into a source of innovation.

Women in the Heian Court: Creativity in Confinement

The Heian period is often romanticized for its aesthetic sensitivity, but it was also a time of strict social hierarchy, particularly for women. Noblewomen were cloistered behind screens and curtains, expected to remain out of sight, to be elegant and composed, and to communicate through poetry or intermediaries. Despite, or perhaps because of, these constraints, Heian women became some of Japan’s most influential literary voices.

With limited public roles, court women turned inward and expressed themselves through literature. Diaries, poetry, and fictional narratives became both a form of personal expression and subtle critique. Alongside Murasaki Shikibu, other women like Sei Shōnagon (The Pillow Book) and Izumi Shikibu wrote with sharp wit, emotional depth, and a uniquely feminine lens on the world around them.

Their work wasn’t just tolerated. It was celebrated. Within the rarefied world of the court, literary brilliance was a kind of social capital. Men and women alike engaged in poetic exchanges, and the ability to write with beauty and emotional intelligence was highly prized. Still, the fact remains: these women were writing from within a world that didn’t fully see them. That Murasaki Shikibu could create a work of such depth and scope under those circumstances is nothing short of revolutionary.

Why The Tale of Genji Still Matters

More than a thousand years later, The Tale of Genji is still widely read, studied, and adapted. In Japan, Murasaki Shikibu is revered in much the same way Shakespeare is in the English-speaking world. The novel has inspired paintings, operas, manga, and even modern retellings.

But beyond its cultural legacy, The Tale of Genji remains a deeply human story. Genji is not a perfect hero. His relationships are often marked by ambiguity, regret, and the passage of time. Characters fall in love, make mistakes, grow old, and die. The novel reflects on impermanence (mono no aware), the beauty and sadness of things that fade, and the struggle to find meaning in a fleeting world.

In many ways, Genji feels timeless because it embraces imperfection. It’s a story full of longing, tenderness, and quiet heartbreak. It invites us to witness not just grand events but subtle changes of the heart.

Three Lessons from The Tale of Genji and Its Author

1. Creative Limits Can Lead to Lasting Innovation

Murasaki Shikibu didn’t have access to the formal language of men’s literature. So she wrote in hiragana, a script considered feminine and less serious at the time. Within those boundaries, she created something enduring. Her work shows that limitations are not the end of creativity. They can be the beginning of something meaningful.

2. Emotional Insight Is Its Own Kind of Strength

The Tale of Genji isn’t about conquest or glory. It’s about relationships, memory, and the passage of time. Murasaki wrote with emotional depth, especially when exploring the inner lives of women. She proved that understanding people can be just as powerful as any grand narrative.

3. Your Story Matters More Than You Think

Murasaki’s voice continues to resonate because she wrote with honesty and care. Her reflections on love, impermanence, and identity still speak to readers today. If you’ve ever questioned whether your story matters, The Tale of Genji is a reminder that your voice has meaning, even if the world doesn’t recognize it right away.

Hopefully you found this as insightful as I did.

From my writing desk to yours,

Stephanie

Recent Posts

The Tale of Genji: The World’s First Novel and the Woman Who Wrote It

Morning Pages 101: What They Are, How They Work, and Why Writers Swear by Them